How to make one into many

In this series, we’ve now arrived here:

Now that we know all about how to add new methods to Hive, lets move out of the scalar world and start thinking in rows!

What does that mean?

Recall that I’m using the term “scalar” to refer to the fact that the data comes in from a single row. So an integer column would be a scalar value here but so too would an array or map even though they technically contain many values inside of the structure. I use this term to emphasize that all the data is together all at once in the worker and not distributed across the cluster. The UDFs in our previous cases can be quite straightforward because they make this assumption across the board. They don’t have to deal with any sort of consolidation of data from sibling workers. It has all the data it needs now and can therefore give a complete answer now.

Given that, lets define UDTF (or User Defined Table Function) as a UDF that takes a scalar value in and gives out a vectorized output. You can think of its purpose as creating a table out of a single, scalar value. This can be enormously useful in the right situations. The most obvious is the built-in Hive UDF ‘explode’ which takes in an array or map of values and turns it into multiple rows alongside all the other columns of that row in the table. This is a great way to literally explode (the name is appropriate!) the value out into the cluster to be aggregated in a distributed fashion any way that you wish. It goes from the single worker mode to a highly distributed effort without requiring a lot of work on your part. Handy! Go see that there are other builtin UDTFS too.

What does that look like?

We can use a UDTF in one of two ways. First, directly in the SELECT clause as the only declared column like this:

SELECT explode(ARRAY(1,2,3)) AS item

Or in a LATERAL VIEW clause like this:

SELECT users.user_info, view1.item FROM users LATERAL VIEW explode(ARRAY(1,2,3)) view1 AS item

Obviously the first case is nice for extremely simple circumstances like testing, but in almost any practical application you’ll want to make use of the lateral view. Especially be aware that we can add the keyword OUTER before the UDTF call to make this more like an outer join in the sense that a row will still be emitted even if the UDTF returns a NULL or empty collection for the input row.

Explosive ideas

We’ll set out to imitate a pretty classic structure in most modern programming languages as our UDTF inspiration. For example, in Kotlin (since that’s our foundational motivation here!) we have a way to do something like:

for(i in 1..5) {

// ...do something with counted index...

}

Logically, this takes the input parameters 1 and 5. It would then produce the sequence: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, stop! Each of these iterations would give the option to do some additional work with that counted index. You could additionally specify a step size like so:

for(i in 1..5 step 2) {

// ...do something with counted odd index...

}

Where now we have the three parameters of 1, 5, and 2. It would produce the sequence: 1, 3, 5.

So, mapping to our Hive UDTF scenario, we will expect to take 1 to 3 parameters and then emit a new row with the index for every item in the sequence as described above. We will allow the one parameter case for implying that you’ll start at one for simple cases. For example, SELECT explode_times(5) would mean the same thing as SELECT explode_times(1,5) and be supported to allow a bit of brevity if the user wishes it.

Calling this with an example response might look like the following:

SELECT explode_times(1,5,2); ==> 1 3 5

Or alternatively:

CREATE TABLE some_junk AS SELECT junk FROM ( SELECT 'junk' AS junk ) one_junk; SELECT iter.index, junk FROM some_junk LATERAL VIEW explode_times(1,5,2) iter AS index; ==> 1, 'junk' 3, 'junk' 5, 'junk'

Make sense? This is actually a super useful method to have around. You can use it to procedurally generate any countable list of things from nothing (i.e., no persisted storage) whenever you wish. It’s like pulling a table from magic. This can be great for testing, but also imagine needing something like a list of the dates of every Tuesday over a range of time from some start date. You could easily generate this by saying something like:

SELECT tuesdays.tuesday AS first_tuesday, iter.num_tuesdays, DATE_ADD(tuesdays.tuesday, iter.num_tuesdays*7) AS num_tuesdays_date FROM ( SELECT '2016-03-22' AS tuesday ) tuesdays LATERAL VIEW explode_times(1,3) iter AS num_tuesdays; ==> '2016-03-22', 1, '2016-03-29' '2016-03-22', 2, '2016-04-05' '2016-03-22', 3, '2016-04-12'

See how we generated that last column from a combination of our countable iterator and the the start date of the column from the original row? Think of all the possibilities!

Full on generic

Recall from the last post that for anything more than a simple scalar UDF in Hive requires that you use their “Generic” base classes which no longer use reflection to make things easy. As such, lets start building a helper class just like we did for tests so that we can keep our main code as clear and readable as possible. Here’s what we’ll start with:

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.ql.exec.UDFArgumentException

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.ObjectInspector

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.primitive.WritableConstantIntObjectInspector

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.primitive.WritableIntObjectInspector

object UDFUtil {

fun expectPrimitive(oi:ObjectInspector, context:String) {

if(oi.category != ObjectInspector.Category.PRIMITIVE) {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context should have been primitive, was ${oi.category}")

}

}

fun expectInt(oi:ObjectInspector, context:String) {

expectPrimitive(oi, context)

if(oi !is WritableIntObjectInspector) {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context should have been an int, was ${oi.javaClass}")

}

}

fun expectConstantInt(oi:ObjectInspector, context:String) {

expectPrimitive(oi, context)

if(oi !is WritableConstantIntObjectInspector) {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context should have been a constant int, was ${oi.javaClass}")

}

}

fun requireParams(context:String, args:Array<Any?>, sizeRange:IntRange, allowNull:Boolean=false):Array<Any> {

if(!sizeRange.contains(args.size)) {

if(sizeRange.first == sizeRange.last) {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context takes ${sizeRange.first} params!")

}

else {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context takes ${sizeRange.first} to ${sizeRange.last} params!")

}

}

if(!allowNull) {

val nullParamIndexes = args.mapIndexed { index, it -> if (it == null) index else null }.filterNotNull()

if(nullParamIndexes.size > 0) {

throw UDFArgumentException("$context requires no null params! (found nulls for params: ${nullParamIndexes.joinToString(", ")})")

}

}

return args.requireNoNulls()

}

}

For now, all this provides are some easy ways to express input requirements for the generic UDF. For instance, we can state things like “we expect this param to be an integer”. As you’ll see in the next section, this simplifies our code a lot! Note that I’m going to hold off being exhaustive for all types and situations here until we actually have a need down the line.

Emit, emit, emit

So lets see what the implementation looks like in code:

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.ql.exec.Description

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.ql.exec.UDFArgumentException

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.ql.udf.generic.GenericUDTF

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.ObjectInspectorFactory

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.StructObjectInspector

import org.apache.hadoop.hive.serde2.objectinspector.primitive.PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory

@Description(

name = "explode_times",

value = "_FUNC_(low, high, incr) - Emits all ints from the low bound to the high bound adding the incr each time",

extended = """

For example, you could do something like this:

SELECT explode_times(3)

==>

1

2

3

or

SELECT explode_times(3, 5)

==>

3

4

5

or

SELECT explode_times(1, 3, 2)

==>

1

3

5

"""

)

class ExplodeTimesUDTF : GenericUDTF() {

override fun initialize(argOIs:StructObjectInspector?):StructObjectInspector {

if(argOIs == null) {

throw UDFArgumentException("Something went wrong, this should not be null")

}

val inputFields = argOIs.allStructFieldRefs

if(inputFields.size < 1 || inputFields.size > 3) {

throw UDFArgumentException("ExplodeTimesUDTF takes 1 to 3 params!")

}

UDFUtil.expectInt(inputFields[0].fieldObjectInspector, "ExplodeTimesUDTF param 1")

if(inputFields.size > 1) {

UDFUtil.expectInt(inputFields[1].fieldObjectInspector, "ExplodeTimesUDTF param 2")

}

if(inputFields.size > 2) {

UDFUtil.expectInt(inputFields[2].fieldObjectInspector, "ExplodeTimesUDTF param 3")

}

return ObjectInspectorFactory.getStandardStructObjectInspector(

listOf("iter"),

listOf(PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory.javaIntObjectInspector)

)

}

override fun process(args:Array<Any?>?) {

if(args == null) return

val safeArgs = UDFUtil.requireParams("ExplodeTimesUDTF", args, 1..3)

// Start at 1 if we only specify a high bound, or take the first param otherwise

val lowBound = if(safeArgs.size > 1) {

PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory.writableIntObjectInspector.get(safeArgs[0])

}

else {

1

}

// End at the first param if it's the only one, or the second if we have more

val highBound = if(safeArgs.size > 1) {

PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory.writableIntObjectInspector.get(safeArgs[1])

}

else {

PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory.writableIntObjectInspector.get(safeArgs[0])

}

// Increment by 1 by default, else use the third param if present

val increment = if(safeArgs.size > 2) {

PrimitiveObjectInspectorFactory.writableIntObjectInspector.get(safeArgs[2])

}

else {

1

}

for(index in lowBound..highBound step increment) {

forward(arrayOf(index))

}

}

override fun close() {}

}

Pretty straightforward, no? You should be able to recognize the structure of the initialize method from the generic sandbox UDF we implemented last time. The initialize method will get run first on the master node to validate what’s getting passed in to the UDF. This way it can fail very fast if the number of parameters or their types are wrong. The initialize method will then get called again once (and only once!) on each worker executing the method. Keep this in mind if you do anything resource intensive here like pulling additional data across the network.

Now pay attention to process. This will get executed once for each input row. Its arguments are the scalar values from the row getting passed into your UDF. At the end, you can see a call to forward() which is the place making zero or more emits for that input row which is what sends this data off into row-oriented land rather than just being a one-to-one mapping.

For everything in between, I’m just mapping those input parameters to the Kotlin range clause in a for loop. See here if you’d like more details about how that works.

Finally, the GenericUDTF base class requires that we define a close() method, but we have no need for it to do anything since we’re not retaining any state or other system resources.

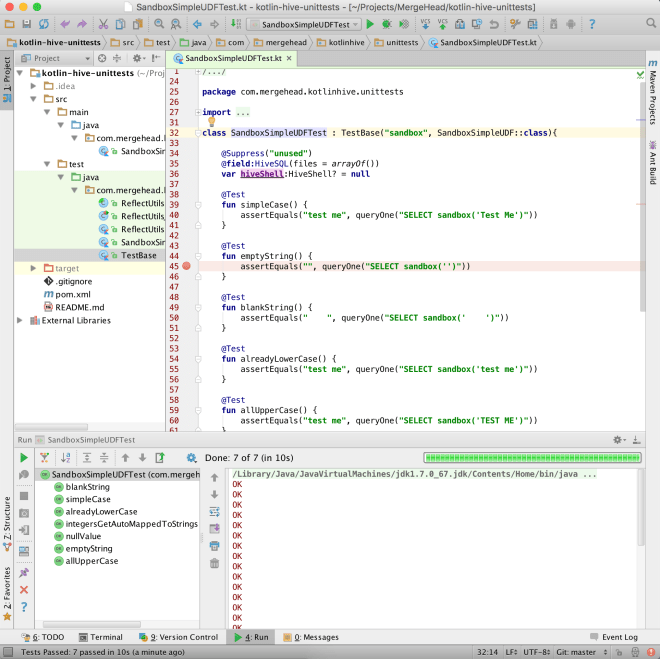

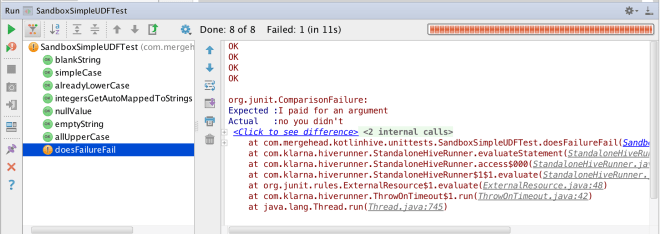

A testing new problem

We’ve actually got a somewhat new scenario to test here. Before, we have always followed the formula:

assertEquals(

expectedStringEncodedResponse,

queryOne("SELECT our_method(constant_input)")

)

However, now we’ll have to follow a pattern more like this:

assertEquals(

listOf(expectedStringEncodedResponse),

query("SELECT our_method(constant_input)")

)

This is because the singular row’s scalar input will now be getting converted to a multi-row table-esque output. Hence the fact that our expectations will now be lists. In our test world, expecting listOf() means Hive table (i.e., calling the helper method query()) and expecting a single object or string means scalar (i.e., calling the helper method queryOne()). Luckily this isn’t much of a change and should be easy to work in to our current design!

Given this, lets dive into the actual tests:

import com.klarna.hiverunner.HiveShell

import com.klarna.hiverunner.annotations.HiveSQL

import org.junit.Assert.*

import org.junit.Test

class ExplodeTimesUDTFTest : TestBase("explode_times", ExplodeTimesUDTF::class) {

@Suppress("unused")

@field:HiveSQL(files = arrayOf())

var hiveShell:HiveShell? = null

@Test

fun simple() {

assertEquals(

listOf("1", "2", "3", "4", "5"),

query("SELECT explode_times(5)")

)

}

@Test

fun simpleRange() {

assertEquals(

listOf("3", "4", "5"),

query("SELECT explode_times(3, 5)")

)

}

@Test

fun rangeWithIncrementAmount() {

assertEquals(

listOf("1", "3", "5"),

query("SELECT explode_times(1, 5, 2)")

)

}

/**

* Nulls are not allowed!

*/

@Test(expected = IllegalArgumentException::class)

fun nullSingle() {

query("SELECT explode_times(NULL)")

}

@Test

fun nonConstantInputIsAllowed() {

assertEquals(

listOf(

"A\t1",

"B\t1",

"B\t2",

"C\t1",

"C\t2",

"C\t3"

),

query("""

SELECT

group,

iter

FROM (

SELECT INLINE(ARRAY(

STRUCT('A', 1),

STRUCT('B', 2),

STRUCT('C', 3)

)) AS (group, dynamic_high)

) data

LATERAL VIEW explode_times(1, dynamic_high) v1 AS iter

""")

)

}

}

The first three test cases follow our examples above and are very straightforward. The only thing really worth noting is that the apparent consistent order of elements here is actually an illusion. Because we’ve broken out into multi-row land, these could all get split across multiple workers. This means that when they finally get re-aggregated to a table’s object files or as input to another step they may be in only partial sorted order or not at all. If you require an order, always state this in your query using a SORT BY or ORDER BY clause so that Hive can make this guarantee. There’s a whole world of discussion about which to choose depending on your needs, so make that choice very carefully (e.g., ORDER BY is very, very painful in terms of efficiency for Hive in almost all but the simplest cases).

The last method illustrates an interesting point. My first crack at writing this for you used my UDFUtil.requireConstantInt() contract enforcement in order to follow my examples. Then I realized that that was restricting things for no good reason! If we just require any int from anywhere instead, then we open the door to taking dynamic input from other sources. This test acts as a great example of verifying that that works, and also future proofs against anyone who makes later changes accidentally reverting back to a constant-only or similar value restriction.

The last example also dives into our new multi-row expectation scenario more. We can see for the first time what’s happening when testing against the shell. For quick behind the scene details, the Klarna HiveRunner uses the CLIDriver class as the entry point (this is the same used when calling hive on the command-line) for all these queries. It can also use the BeeLine class instead if you wanted so simulate using a Beeline client. If you wish to do the latter, then you must re-build the HiveRunner jar with the -DcommandShellEmulation=BEELINE option set for Maven. See their github page here for more details. This is obviously a pain, but if it’s a real need for you it can be worth it!

Given all that, this explains why we’re seeing rows of tab-separated value columns. This is literally exactly the same thing you’d be getting if you did this:

kotlin-hive-udtfs$ mvn clean package

...

kotlin-hive-udtfs$ cd target/

target$ hive

...

hive> ADD JAR jars/kotlin-runtime-1.0.1.jar;

Added [jars/kotlin-runtime-1.0.1.jar] to class path

Added resources: [jars/kotlin-runtime-1.0.1.jar]

hive> ADD JAR jars/kotlin-stdlib-1.0.1.jar;

Added [jars/kotlin-stdlib-1.0.1.jar] to class path

Added resources: [jars/kotlin-stdlib-1.0.1.jar]

hive> ADD JAR kotlinhive-udtfs-1.0.0.jar;

Added [kotlinhive-udtfs-1.0.0.jar] to class path

Added resources: [kotlinhive-udtfs-1.0.0.jar]

hive> CREATE TEMPORARY FUNCTION explode_times AS 'com.mergehead.kotlinhive.udtfs.ExplodeTimesUDTF';

OK

Time taken: 0.39 seconds

hive> SELECT

> group,

> iter

> FROM (

> SELECT INLINE(ARRAY(

> STRUCT('A', 1),

> STRUCT('B', 2),

> STRUCT('C', 3)

> )) AS (group, dynamic_high)

> ) data

> LATERAL VIEW explode_times(1, dynamic_high) v1 AS iter;

Query ID = user_20160331075858_ae82d389-2e50-4e32-a712-2a6144a66bf9

Total jobs = 1

Launching Job 1 out of 1

Number of reduce tasks is set to 0 since there's no reduce operator

Job running in-process (local Hadoop)

Hadoop job information for Stage-1: number of mappers: 0; number of reducers: 0

2016-03-31 07:58:23,169 Stage-1 map = 100%, reduce = 0%

Ended Job = job_local106521103_0001

MapReduce Jobs Launched:

Stage-Stage-1: HDFS Read: 0 HDFS Write: 0 SUCCESS

Total MapReduce CPU Time Spent: 0 msec

OK

A 1

B 1

B 2

C 1

C 2

C 3

Time taken: 2.915 seconds, Fetched: 6 row(s)

See? Same output! Each row there is an entry in the list, and each entry contains a string of the string encoded column values separated by the default column separation value (i.e., tab). And doesn’t this process look exactly like that first verification we did in the intro post? Coincidence?!

Onwards!

You can find all the code used in this post here. And with that, you now have another new tool in your Hive belt. You can use these for all manner of things beyond these simple examples. For instance, imagine having an ETL created denormalized scalar user object containing lots of random, poorly formatted info. You could use something like this to crawl all over that model and emit the interesting attributes you discover. Then back on the Hive level you can aggregate these attributes however you wish to look for interesting, emergent patterns out of that population. For example, something like this:

SELECT cool_observation, COUNT(*) AS num_users, SUM(how_much) AS how_much_they_did_it FROM users LATERAL VIEW make_cool_observations(denormed_data) v1 AS cool_observation, how_much GROUP BY cool_observation

Hive will scale the execution of both the explosion of the observations and the aggregated counts very efficiently across all the available hardware. Very handy!

That’s just some food for thought to tide you over until next time. Then we’ll be working with UDAFs. The excitement!